Introduction

Seizures are a common cause of visit to the emergency department (ED). A seizure is a paroxysmal event due to abnormal, excessive, hypersynchronous electrical discharges from cerebral cortex. The clinical manifestations can vary from convulsive activity to experiential phenomena that may not be readily discerned by an observer. Although a variety of factors influence the incidence and prevalence of seizures, 5 to 10% of the population will have at least one seizure, with the highest incidence occurring in early childhood and late adulthood. One estimate indicates that approximately 1% of patients coming to the ED do so because of seizures.1 Using the definition of epilepsy as two or more unprovoked seizures, the prevalence of epilepsy has been estimated at 5 to 10 persons per 1000.2

Differential diagnosis of seizure

A variety of conditions can mimic seizures (Table 1). In most cases seizures can be distinguished from other conditions by meticulous attention to the history and relevant laboratory studies. The core features that distinguish seizures from other conditions are the disturbance in consciousness, stereotyped and reproducible nature of phenomenology. On occasion, additional studies, such as video- electroencephalograph (EEG) monitoring, sleep studies, tilt table analysis, or cardiac electrophysiology, may be required to reach a correct diagnosis. Two of the more common nonepileptic syndromes in the differential diagnosis are detailed below.

Syncope

A generalized seizure needs to be differentiated from syncope. Characteristics of a seizure include the presence of an aura, cyanosis, unconsciousness, motor manifestations lasting >30 seconds, postictal disorientation, muscle soreness, and sleepiness. In contrast, a syncopal episode is more likely if the event was provoked by acute pain or anxiety or occurred immediately after arising from recumbent or sitting position. 3 Patients with syncope often describe a stereotyped transition from consciousness to unconsciousness that includes tiredness, sweating, nausea, tunneling or graying of vision, and they experience a relatively briefer loss of consciousness. Headache, spasms of extremities or incontinence usually suggests a seizure but can rarely occur if syncope is prolonged. Syncope is more common in elderly people. 23% of people over age 70 years experience a syncopal episode over a 10 year period, compared with 15% of those under 18 years. 4 A brief period (i.e., 1 to 10s) of convulsive motor activity is occasionally seen at the onset of a syncopal episode, especially if the patient had remained in an upright posture after fainting and therefore had a sustained cerebral hypoperfusion. Convulsive syncope, happens in around 12% of patients presenting with syncope. 4 A video study of the clinical features of syncopal attacks induced in healthy volunteers showed that myoclonus happens commonly in syncope, and that other movement more commonly seen in epilepsy, such as automatisms and head turning, also occur. 5

Psychogenic non epileptiform seizures (PNES)

Psychogenic seizures are nonepileptic behaviors that resemble seizures (Table 2). They are often part of a conversion reaction precipitated by underlying psychological distress. Certain behaviours, such as side-to-side turning of the head, asymmetric and large-amplitude shaking movements of the limbs, twitching of all four extremities without loss of consciousness, and pelvic thrusting are more commonly associated with psychogenic rather than epileptic seizures.6 Compulsive eyelid screwing is often seen in psychogenic attacks. However, the distinction is occasionally difficult on clinical grounds alone, since the behavioural manifestations of seizures especially of frontal lobe origin can be extremely unusual, and in both cases the routine surface EEG maybe normal. 7 In one study a total of 330 PNES from 61 patients were analysed and based on semiology six different patterns were observed. In a given patient, all the seizures belonged to a single pattern of PNES in 82% of cases. Contrary to common belief, PNES demonstrated stereotypy both within and across patients. 8 Video-EEG monitoring is often useful when history is nondiagnostic. The diagnosis of psychogenic seizures does not exclude a concurrent diagnosis of epilepsy, since the two often coexist in 10% to 30% of patients. 9, 10

Approach to a Patient with Seizure

History

Seizures frequently occur out-of-hospital, and the patient may be unaware of the ictal and immediate postictal phases; it would be valuable to seek information from an eyewitness in person or by telephone. Seizures may be either focal or generalized. Focal seizures are those in which the seizure activity is restricted to discrete areas of the cerebral cortex. Focal seizures occur within discrete regions of the brain. If consciousness is fully preserved during the seizure, the clinical manifestations are considered relatively simple and the seizure is termed a simple focal seizure. If consciousness is impaired, the symptomatology is more complex and the seizure is termed a focal seizure with impaired awareness earlier known as complex partial seizures (CPS). An important additional subgroup comprises those seizures that begin as focal and then spread diffusely throughout the cortex, i.e., focal seizures with secondary generalization. Focal seizures are usually associated with structural abnormalities of the brain. In contrast, generalized seizures may result from biochemical or structural abnormalities that have a more widespread distribution. Generalized seizures involve diffuse regions of the brain simultaneously. Patients with seizures often give a past history of febrile seizures, isolated aura that were unrecognized or family history of seizures. Epileptogenic factors such as prior head trauma, stroke, tumor, or vascular malformation of the brain may be present. In children, impairment in developmental milestones may indicate the presence of an underlying CNS disease. Precipitating factors such as sleep deprivation, systemic diseases, metabolic derangements, acute infection, drugs that lower the seizure threshold or alcohol or illicit drug use should also be explored. 3 Patients with cardiac disorders can cause a diagnostic dilemma as they are predisposed to cardiogenic syncopal attacks as well as seizures secondary to brain abscess (in the case of cyanotic heart diseases or infective endocarditis) or cardioembolic stroke (in the case of valvular heart disease or cardiac arrhythmia).

Examination

The general physical examination can provide valuable clinical clues and should include a search for signs of infection, malignancies or intoxication. Look for signs of neurocutaneous disorders, such as tuberous sclerosis or neurofibromatosis, or chronic liver or renal disease. Presence of organomegaly may indicate a metabolic storage disease or lymphoreticular malignancy, while limb asymmetry may provide a clue to brain injury early in development. Signs of head trauma and use of alcohol or illicit drugs should be sought. 3 Auscultation of the heart and carotid arteries may identify an abnormality that predisposes to cerebrovascular disease.

Laboratory studies

Routine blood studies are indicated to identify the more common metabolic causes of seizures, such as abnormalities in electrolytes, glucose, calcium, magnesium, and hepatic or renal disease. A screen for toxins in blood and urine should also be obtained from all patients in appropriate risk groups, especially when no clear precipitating factor has been identified. A lumbar puncture is indicated if there is any suspicion of meningitis or encephalitis and is mandatory in all patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), even in the absence of symptoms or signs suggesting infection.

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

The diagnosis of a seizure is based on the clinical history and not necessarily on the EEG. This neurologic tenet is based on the fact that many individuals with seizures have normal interictal EEGs. In addition, the sensitivity of an interictal EEG for different seizure types is highly variable. All patients who have a possible seizure disorder should be evaluated with an EEG as early as possible. The absence of electrographic seizure activity does not exclude a seizure disorder because epilepsia partialis continua (EPC) may originate from a region of cortex that is not within the range of the scalp electrodes. The ictal EEG is always abnormal during generalized tonic-clonic seizures. 11 For suspected seizures of temporal lobe origin, the use of additional electrodes beyond the standard scalp locations (e.g., sphenoidal electrodes) may be required to localize a seizure focus. 12 Since seizures are typically infrequent and unpredictable, it is often not possible to obtain the EEG during an ictus. Continuous monitoring for prolonged periods by video-EEG telemetry units or by portable ambulatory units has made it easier to capture the clinical characteristics of the ictus. A single interictal EEG may show epileptiform discharges in about half of patients with epilepsy. Rarely epileptiform activity may be seen in persons with migraine, past history of epilepsy (Benign Childhood Epilepsy) or unaffected family members of persons with epilepsy. The EEG is useful for classifying seizure disorders and for selecting appropriate antiepileptic drugs.

Multiple recordings increase the diagnostic yield of the EEG; while approximately 30 to 50 percent of patients with epilepsy demonstrate epileptiform abnormalities on the first EEG, the yield increases to 60 to 90 percent with repeated recordings. Various manoeuvres increase the likelihood of recording epileptiform discharges, including sleep deprivation before the study, recording a portion of the EEG as the patient sleeps, recording the EEG as the patient hyperventilates for several minutes, and subjecting the patient to stroboscopic photic stimulation during the study. The EEG is also helpful in assessing the risk of seizure recurrence. A prospective study of EEGs performed in patients with untreated idiopathic first seizures found that the presence of epileptiform abnormalities on EEG was associated with a recurrence risk of 83 percent, compared with 41 percent in patients with nonspecific abnormalities and 12 percent in patients in whom routine and partially sleep-deprived EEGs were normal.13

Importance of brain imaging in evaluation of new-onset seizures

Almost all patients with new-onset seizures should have a brain imaging study to evaluate the underlying structural abnormality. 14 The only potential exception to this rule is children who have an unambiguous history and examination suggestive of a generalized seizure disorder such as absence epilepsy. Computed tomography (CT) scan of head, carried out in the emergency department for a patient presenting with seizure, resulted in a change of acute management in 9 to 17% of adults and 3 to 8% of children.15 Frequent abnormalities detected in the CT scan in adults in such instances included traumatic brain injury, subdural hematomas, nontraumatic bleeding, cerebrovascular accidents, tumors and brain abscesses while cerebral hemorrhages, tumors, cysticercosis or obstructive hydrocephalus predominated in children. Persons with AIDS and first seizures have very high rates of CT abnormalities, which included cerebral atrophy, mass lesions, CNS toxoplasmosis, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). 16

The clinical characteristics predictive of an abnormal CT scan for patients presenting with seizures in the emergency department were age less than 6 months or age greater than 65 years, history of cysticercosis, altered mentation, closed head injury, recent CSF shunt revision, malignancy, neurocutaneous disorder, human immunodeficiency virus infection and seizures with focal onset or duration longer than 15 minutes. 15

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been shown to be superior to CT for the detection of cerebral lesions associated with seizures (Table 3). Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), has increased the sensitivity for detection of abnormalities of cortical architecture, including hippocampal atrophy associated with mesial temporal sclerosis, and abnormalities of cortical neuronal migration. In a patient with a suspected CNS infection or mass lesion, CT scanning should be performed emergently when MRI is not immediately available. 17, 18

Evaluation of a patient with epilepsy who presents with a break through seizure

The common causes of break through seizures in patients with epilepsy are noncompliance (most common), sleep deprivation, concomitant use of other medications or stress factors.

A patient with known epilepsy who has had a single, habitual seizure and whose mental status has returned to baseline need not be transported to the ED unless other injuries require treatment.19 If the patient arrives at the ED, only testing of the anticonvulsant level is necessary. "Routine" lab work and neuroimaging are not necessary if the patient has returned completely to baseline and has no significant head injury caused by the seizure. If anticonvulsant levels are low, particularly if below the patient's usual levels, he or she will need a partial or full loading dose of the anticonvulsant.20 The following is a convenient formula for determining how much of the drug to give the patient: Dose (mg) = weight (kg) X volume of distribution for the drug (L/kg) X [the desired level – the current level (mcg/mL)]. If the specific patient's optimal levels are unknown, reasonable target levels are at the upper end of the usual therapeutic ranges (Table 4). 21, 22 Intravenous loading can be performed with phenobarbital, phenytoin/fosphenytoin, valproate, or levetiracetam.

'Therapeutic' Drug Levels

It is now possible to estimate the blood level of several antiepileptic drugs in clinical practice. These results should be interpreted in the clinical context only. Changing the dosage of anti-epileptic drugs solely on the basis of a serum drug level is to be avoided. 22 Therapeutic drug levels are established by animal and human studies, the latter involving patients with refractory seizures who are generally taking multiple anticonvulsants. Thus, the serum drug concentration that is effective in an individual with infrequent seizures has not yet been established and may be lower than the usual reported therapeutic level. Serum drug levels are primarily helpful in, determining compliance, when patients are on dialysis, in pregnancy where drug levels of anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) like lamotrigine can precipitously fall in the third trimester, documenting a level at which a therapeutic failure (i.e., seizure) has occurred, analyzing drug-drug interactions and assessing side effects.

Patient with no history of epilepsy who has returned to baseline following a seizure

This patient should be taken to the specialist and evaluated which should include basic biochemical studies (Table 5), and a toxicology screen which must include an alcohol test if available. 3 The American College of Emergency Physicians’ (ACEP) guidelines advise determining only a serum glucose and sodium level on patients with a first-time seizure with no co-morbidities who have returned to their baseline. 23 A pregnancy test should be obtained if a woman is of childbearing age. All patients who present with seizure for the first time deserve a brain imaging. 24 An emergent CT scan of the head may not be necessary if there is no serious head injury, the neurological examination is normal and the patient had made a quick recovery from the seizure. 25 In such instances a CT scan is unlikely to show an abnormality that requires emergent intervention such as a space-occupying lesion.

Regardless of whether a CT scan is done, the patient who had a recent seizure for the first time deserves an MRI of the brain, as the latter is much more sensitive in detecting structural lesions related to epilepsy. 26 The patient also requires an EEG. An EEG performed soon after the event is more likely to show an abnormality than one performed later. 27 EEG after sleep deprivation increases the yield in detecting epileptiform abnormalities, 28 although background abnormalities may be obscured by excessive drowsiness.

After a single unprovoked seizure, the chance of a second seizure (ie, likelihood of going on to develop epilepsy) varies. A first seizure caused by an acute disturbance of brain function (acute symptomatic or provoked) is unlikely to recur (3-10%). If a first seizure is unprovoked, however, meta-analyses suggest that 30-50% will recur; and after a second unprovoked seizure, 70-80% will recur, justifying the diagnosis of epilepsy (a tendency for recurrent seizures). 29, 30 The patient with a single seizure who has returned to baseline does not need to be started on an antiepileptic drug in the ED. 31 Treatment does lower the rate of recurrence, but patients who would not have had a recurrent seizure are subjected needlessly to the potential toxicity of these medications. Recurrence is more likely in those with a history of significant head injury or other CNS insult. If the patient has a normal MRI and EEG, the likelihood of a second seizure is approximately 1 in 3; if either test result is abnormal, the chances are approximately 1 in 2; if both are abnormal, the probability rises to 2 in 3. 32

In a meta-analysis 32 of 16 studies with median follow-up ranging from one to five years, the risk of seizure recurrence following an unprovoked seizure was 51 percent. The two most important prognostic factors influencing risk of recurrence included etiology of the seizures and EEG findings.33, 34 Patients whose seizures were likely symptomatic of remote cerebral injury were more likely to experience recurrence than those whose seizures were judged to be idiopathic, with two-year recurrence risks of 57 percent versus 32 percent. 32 This information helps to individualize treatment and counselling after a patient's first seizure (Table 6).

Patient with no history of epilepsy who does not return to baseline following seizure

These patients during the postictal period are confused or lethargic which usually lasts 20-30 minutes. If the postictal state is longer than this or a new focal neurological abnormality is detected, perform a CT scan of the head as soon as possible. Unless contraindicated a lumbar puncture also should be performed to look for evidence of bleeding or infection. Prolonged postictal confusion suggests either ongoing seizure activity or encephalopathy due to toxic, metabolic, infectious, or structural damage. If available, an urgent EEG can discriminate between ongoing seizure activity (ie, non-convulsive status epilepticus) and encephalopathic state.

Treatment of seizures

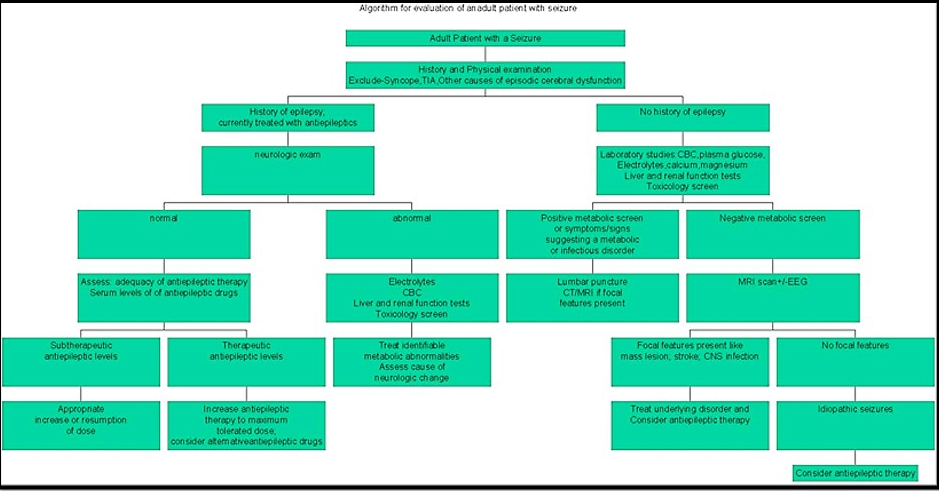

When the patient brought to OPD is not acutely ill, the initial evaluation should focus on whether there is a history of earlier seizures (Figure 1). Both National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidelines advocate that AEDs should only be commenced after a first seizure on the advice of an epilepsy specialist, and then, only if an EEG shows unequivocal epileptic discharges, if the patient has a congenital neurological deficit, if the patient and physician consider the risk of recurrence to be unacceptable (>60% recurrence risk over next 10 years) or if brain imaging shows a structural abnormality (NICE only). 35, 36 The American College of Emergency Physicians recommend that patients with a normal neurological examination, no co-morbidities, and no known structural brain disease do not need to be started on an AED immediately. 37

If drug treatment is considered, which drug is preferred?

If drug treatment is considered after a first seizure, and if the underlying seizure types have been established, the following antiepileptic drugs are preferred (Table 7).

It is recommended that individuals should be treated with a single antiepileptic drug (monotherapy) wherever possible.38 If an AED has failed because of adverse effects or continued seizures, a second drug should be started (which may be an alternative first-line or second-line drug) and built up to an adequate or maximum tolerated dose and then the first drug should be tapered off slowly as warrented. It is recommended that combination therapy (adjunctive or ‘add-on’ therapy) should only be considered when attempts at monotherapy with AEDs have not resulted in seizure freedom. Advise the patient not to operate a motor vehicle for the length of time required by state law and to avoid any activities or situations during which sudden loss of consciousness would be dangerous. Doctors should record in the medical notes that this advice has been given, but audits of medical records show that in only 0.9–21% of cases was it documented that such advice had been given. 39

Treatment with AED therapy is a must after a second seizure. 36 Drug choice should be individualised, and consideration given to factors such as teratogenicity, the patient’s cognitive abilities, drug interactions, and cost. Therapy for a patient with epilepsy is multimodal and includes treatment of underlying conditions that cause or contribute to the seizures, avoidance of precipitating factors, and addressing a variety of psychological and social issues.40 NICE recommend that all people having a first seizure should be seen within 2 weeks by a specialist in the management of the epilepsies to ensure precise and early diagnosis. 36 Issues such as employment or driving may influence the decision whether or not to start medications as well.

Table 1

Various conditions that may resemble seizure

Table 2

Clinical features to differentiate epileptic from psychogenic non epileptiform seizures

Table 3

ssential diagnostic procedures in patients with a first seizure

Table 4

Pharmacokinetic data on antiepileptic drugs

Table 5

Blood investigations in a patient with 1st episode of seizure.

|

|

Random Blood Sugar |

|

|

Electrolytes-Sodium, Potassium, Calcium, Magnesium |

|

|

Complete Blood Count |

|

|

Renal Function Test, Liver Function Test |

|

|

Arterial Blood Gas |

Table 6

Reported risk factors for seizure recurrence

Table 7

Antiepileptic drugs preferred for different seizures

Newer AEDs after first episode of seizure

Newer antiepileptic drugs have several favourable pharamacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics when compared to older AEDs. Most of them have longer duration of action and fewer drug interactions. In older patients among newer AEDs lamotrigine is very effective based on percentage of patients who are seizure-free for 12 months, while sustained release carbamazepine may have comparable effectiveness. Valproate treatment appears to be effective in refractory cases while oxcarbazepine is considerably less effective than other AEDs in elderly. 41

Treatment of underlying conditions

If the sole cause of a seizure is a metabolic disturbance its reversal is the key management. Therapy with antiepileptic drugs is usually unnecessary unless the metabolic disorder cannot be corrected promptly and the patient is at risk of having further seizures. If the apparent cause of a seizure was a medication (e.g., theophylline) or illicit drug use (e.g., cocaine), then appropriate therapy is avoidance of the drug. There is usually no need for antiepileptic medications unless subsequent seizures occur in the absence of these precipitants. 3 Seizures caused by a structural CNS lesion such as a brain tumor, vascular malformation, or brain abscess may not recur after appropriate treatment of the underlying lesion. Despite removal of the structural lesion, there is a risk that the seizure focus will remain in the surrounding tissue or develop de novo as a result of gliosis and other processes induced by surgery, radiation, or other therapies. 42 Several experts prefer to keep most patients on an antiepileptic medication for at least one year, and attempt to withdraw medications only if the patient has been completely seizure-free.

Women, contraception, AEDs and seizures

If a woman taking enzyme-inducing AEDs chooses to take the combined oral contraceptive pill, a minimum initial dose of 50 micrograms of oestrogen is recommended. If breakthrough bleeding occurs, the dose of oestrogen should be increased to 75 micrograms or 100 micrograms per day, and ‘tricycling’ (taking three packs without a break) should be considered. The progesterone-only pill is not recommended as reliable contraception in women taking enzyme-inducing AEDs. Women taking enzyme-inducing AEDs who choose to use depot injections of progesterone should be recommended for a shorter repeat injection interval (10 weeks instead of 12 weeks). The progesterone implant is not recommended in women taking enzyme-inducing AEDs. The use of additional barrier methods should be discussed with women taking enzyme-inducing AEDs and oral contraception or having depot injections of progesterone. If emergency contraception is required for women taking enzyme-inducing AEDs, the dose of levonorgestrel should be increased to 1.5 mg and 750 micrograms 12 hours apart. 36

Avoidance of precipitating factors

Sleep deprivation should be avoided. Women with catamanial exacerbation of seizures can be managed with pulse dose of clobazam during the period of higher risk. Patients who tend to get seizures after use of alcohol should preferably avoid its use. 3 There are also relatively rare cases of patients with seizures that are induced by highly specific stimuli such as a video game, monitor, music, or eating (“reflex epilepsy”). 43, 44

Conclusion

The diagnosis of seizures is clinical and investigations are only adjutant. MR imaging has an important role in evalution. Among newer AEDs lamotrigine is very effective in older patients while sustained release carbamazepine may have comparable effectiveness. The emphasis of management is long term and team delivered.