Introduction

Brain is a dynamic organ contains billions of trillions of `neuronal cells` which continuously adapts and changes in response due to changes in the external and internal environmental impacts. Neural signals of such brain cells are massively curved immense data streams (voluminous signals and images) contain information about the understanding brain activity. Specifically, movement and movement intentions are encoded in the motor cortex, cerebral cortex and brainstem regions. This property of the brain, which is also called brain dexterity or more conversely plasticity, allows learning. It also facilitates recoveries from injuries and damages to the brain particularly to the neurons of subthalamic nuclei (STN), global pallidus interna, externa (GPi, GPe), substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc), substantia nigra pars reticulate (SNpr), putamen, and many other neurons. Basal ganglion is central part of the brain with distinct circuits that link many parts of brain. Its functional architecture is parallel in nature and characteristic of the organization within each individual circuit. It is interlinked with several neurons of cerebral cortex, thalamus, brainstem, and at several other areas of brain coupled with a variety of functions, such as motor learning, control-of-voluntary motor-movements, procedural-learning, routine-behaviors-of-habits (bruxisms), eye-movements, action, cognition, emotion, thought, perception and motor controls. Experimental—studies shown that the basal-ganglia exert an inhibitory influence on a number of motor neurons, and that a release of this inhibition permits a motor neuron to become active. The behaviour switching that takes place within basal ganglia is influenced by voluminous signals (big data) of sensory motor neurons from many components of the brain, including prefrontal cortex which plays a fundamental key role in executive-functions.1 Parkinson`s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disease caused by a complex interaction of loss of dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic neuromuscular systems.2 Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by hallmark motor symptoms.1 four primary symptoms: convolution of resting tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia and postural instability,3 multi-factorial disorder with high-penetrant mutations accounting for small percentage of PD. The search for optimal cure is on for the past 2 centuries ever since the time it was first described by James Parkinson.4

At present there is no definitive test for PD and diagnostics (the diagnosis) are based on the presence of clinical and/or diagnostic symptoms and the response to antiparkinsonian medicine. The most established scale for assessing disability and impairment in PD is the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS)5 scores and scales are given in Table 1 together with modified system (addendum of stages 1.5 and 2.5) to help describe the intermediate course of the disease, Appendix-I, which is based on subjective clinical evaluation of symptoms.6, 7, 8 A need therefore exists to quantify PD characteristics objectively, in order to improve the diagnosis, define disease subtypes, monitor disease progression and demonstrate behaviour—treatment efficacy.9, 10

Table 1

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is one method for Parkinson diseased conditions that uses low amplitudes and high frequency electrical pulses to stimulate the subthalamic nucleus and its connected associated brain regions, such as global pallidus (interna and externa), substantia nigra (pars compact and pars reticulate) , putamen, etc. Even though, the mechanisms of DBS action are uncertain, correct electrode placement and stimulation programming may improve motor symptoms (i.e. reduce tremor, rigidity and bradykinesia) and allow for a reduction in antiparkinsonian medicine doses. However, DBS stimulation parameters are set by subjective evaluation of symptoms, and no physiological-based quantitative measures (such as amplitude, frequency, pulse-width, etc) are used to optimize the efficacy of DBS in reducing motor disorders.11 It is those measurements that enable the objective quantification of neuromuscular function and movement, hence, may be used for quantifying the effects of DBS, antiparkinsonian medicine or other treatments.

The main pathology of Parkinson’s disease is present in the nigrostriatal system which is characterized by the degeneration of the dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (and pars reticulate) resulting in the disruption of putamen circuit thus manifesting in the form of tremors, rigidity, bradykinesia/akinesia, and postural instability. Substantia nigra pars compacta is a part of the basal ganglia which modulates the cortex and helps in fine tuning motor activities.

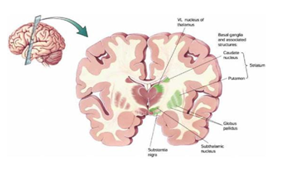

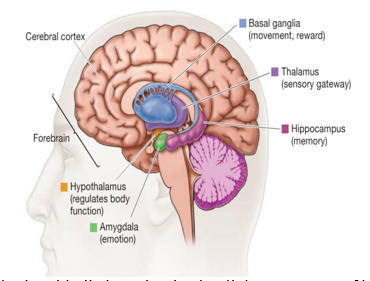

Basal ganglion is an important key and central area of the brain with distinct circuits that link many parts of brain (Figure 1). Its functional architecture is parallel in nature and characteristic of the organization within each individual circuit. It is interlinked with several neurons of cerebral cortex, thalamus, brainstem, and at several other areas of brain coupled with a variety of functions, such as motor learning, control-of-voluntary motor-movements, procedural-learning, routine-behaviors-of-habits (bruxism), eye-movements, action, cognition, emotion, thought, perceptual abilities and motor-controls.

Figure 1

Basal ganglion and its keyarea of the brain with distinct circuits that link many parts of brain

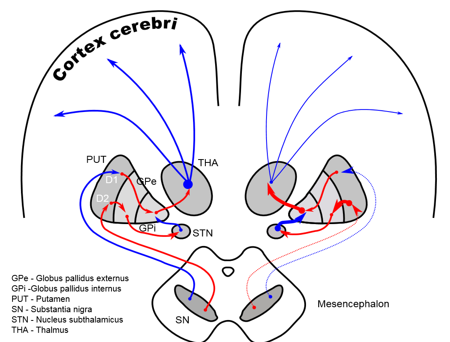

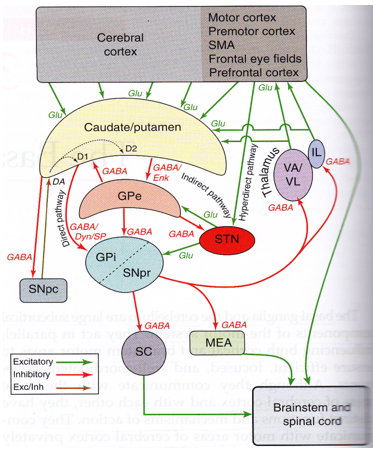

Experimental—studies shown that the basal-ganglia exert an inhibitory influence on a number of motor neuron systems, and that a release of this inhibition permits a motor neuron to become active. The behavior switching that takes place within basal ganglia is influenced by voluminous signals (massive data) of motor neurons from many components of the brain, including prefrontal cortex which plays a fundamental key role in executive function. Its characteristics are affected by many factors including diseases, such as Parkinson, Huntington, chorea, Writer`s musicians cramp and also a number of other diseases. Its functional architectures parallel in nature, consists of sub-cortical-nuclei (SCN) in the brains of vertebrates situated at forebrain, caudate nucleus, putamen, globus pallidus and substantia-nigra(SN) (Figure 2) that are complex-neural-structure correlated with motoneuron function. It receives afferents from motor cortex and drives efferents to thalamus cortex, controls motorneuron impulses (dirac-delta-functions) from cortex to spinal-cord.

Figure 2

Simplified schematic wiring diagram of basal ganglia circuit. Excitatory connections are indicated by green arrows, inhibitory connections by red arrows, and the modulatory dopamine projection is indicated by a red and green arrow.

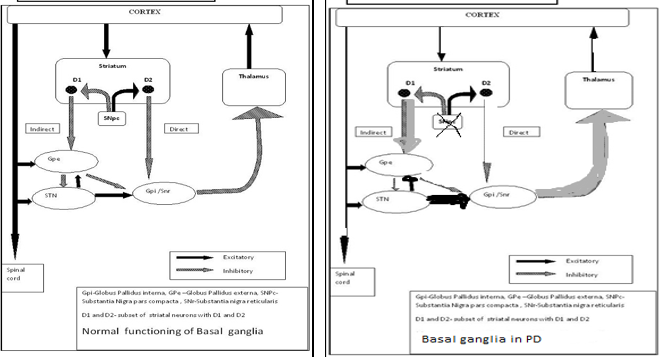

The complex fine movements are coordinated by BG. In the failure of the BG, impulsive contraction occur in extremity dexterous muscle. The significance of those SCN for normal functional brain behavior is stressed by numerous diverse neurological conditions coupled with basal-ganglia dysfunction leading to many disorders of the behavior control, such-as, Parkinson, dystonia/dystonic writer’s cramp (dWCs), Tourette syndrome, obsessive compulsive, hemiballismus, Huntington’s disease and a myriad of other movement disorders, a major health hazard causing to death. There are two dopaminergic metabolic pathways (with PD risk) involved form the striatum to the thalamus and the cortex- direct pathway which leads to stimulation of the cortex and the indirect pathway which inhibits the cortex. The dopaminergic supply from the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) acts by D1 receptors which activate the direct pathway and the D2 receptors which inhibit the indirect pathway. Absence of these neurons leads to an increased firing from the subthalamic and globus pallidal interna (GPi) neurons which leads to increased inhibition of the thalamic neurons and cortex and overall reduced movement.12 Figure 3 depicts the normal functioning of basal ganglia and the abnormality in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease.

Figure 3

The normal functioning of basal ganglia and the abnormality in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease

The advent of action with initial levodopa followed by the armamentarium of various remedies but the medical behaviour is laden and/or fraught with appearance of various side effects such as dyskinesias and on-off phenomenon. The dopaminergic drive in normal patients is a continuous one and oral medications however cannot completely mimic the normal state with drug concentrations changing from trough to peak levels based on the time of consumption. Initial ablative surgeries performed during the 1950s targeting the globus pallidus interna and thalamus improved with the onset of stereotactic surgery and deep brain stimulation techniques. This involves inhibition of the brain structures with high frequency oscillations usually of the frequencies ranging from 130 to 190 Hz. This high frequency inhibition of neurons in two structures –subthalamic nucleus and globus pallidus interna has improved symptoms in subjects (patients) with Parkinson’s disease and has become the standard of care in advanced disease.13, 14 Further, on head to head comparison of the therapeutic options, a recent study has shown that DBS is more effective than the best medical therapy in improving "on" time without troubling dyskinesias by 4.6 hours per day (4.6h/day), motor function in 71% v/s 36% on medical therapy, and in quality of life, 6 months after surgery.15, 16 Of the two, subthalamic nucleus (STN) stimulation is associated with more drug reduction compared to globus pallidal stimulation. Subthalamic nuclei deep brain stimulation (STN DBS) involves placing two leads, one in each subthalamic nucleus with a pulse generator placed under the skin on the chest. The surgery is performed under stereotactic guidance –i.e., a stereotactic frame is placed on the head and the nucleus is identified on the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and the co-ordinates are obtained in the vertical and the horizontal planes, then with the help of these co-ordinates the leads are placed through a small hole on the scalp. Table 2, Table 3 illustrate the lead implantation in the location, observation of MER and the corresponding effect of stimulation and the correlational observations made intra-operatively with possible electrode position.

Table 2

Is the led (the electrode) in the correct place at correct point?

Table 3

Correlation of Observations Made Intra-operatively with Possible Electrode Position

For optimal therapeutic efficacy of DBS, it is imperative to have accurate electrode lead placement. 17 A small deviation in the electrode positioning may cause it to be misplaced in the surrounding structures such as the corticospinal tract, red nucleus, occumulotor nerve and other structures. Improper targeting may lead to various side effects such as speech disorders, visual deficits with diplopia, ocular deviations or motor stiffness.17

Experimental Set-Up

We setup an MER amplifier having an input impedance 1.1±0.4 MΩ; Extracellular single/multi-unit MER was performed with small (10 μm width) polyamide-coated tungsten microelectrodes (Medtronic; microelectrode 291; measured at 220 Hz, at the beginning of each trajectory) mounted on a sliding cannula. Signals were recorded with the amplifiers (10,000 times amplification) of the LeadPoint system (Medtronic), using a bootstrapping principle and were filtered (analog band-passed) between 500 and 5,000 Hz (−3 dB; 12 dB/oct) with 12 kHz sampling frequency using a 16 bit analog to digital (A⁄D) converter and then up-sampled at 24 kHz off-line. After the electrode movement cessation, a 2 seconds signal stabilization period was followed. Multi-unit segments were recorded for the duration of 5–20 seconds. Approximately, 8 and 12 mm above the MRI-based target, the microelectrodes were advanced in steps of 500 μm towards the target by a manual microdrive for the STN neurons. While the needles were inside the STN, the spiking activity of the neurons lying close to the needle (pick-up area up till 200 μm) could be recorded, at each depth. Depending on the neuronal density not more than 3–5 signal units were recorded simultaneously. More distant units could not be distinguished from the background level. Subthalamic nuclei (STN) relatively a small biconvex lens structured almond lens-shaped nucleus in the brain where it is, from a functional point of view, component of the basal ganglia system (an organ of the brain). In terms of anatomy, it is the major part of the subthalamus, was first described by Jules Bernard Luys in 1865.18 Damage to the STN neurons causing larger involuntary movements and therefore attacking Parkinson`s disease (PD). DBS is one effective empirical method for subjects with such disease, advanced idiopathic PD, etc.

High frequency deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subthalamic nucleus (STN) is an effective treatment for patients with Parkinson`s disease.19, 20, 21 The DBS technique has been further refined throughout the years by improved magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques, advanced neuro-physiological recording possibilities, and advances in hardware and software technology.22 To perform MER in STN-DBS, five MER/macrostimulation needles were placed in an array with a central, lateral, medial, posterior, and an anterior position placed 2 mm apart, to delineate the borders of the nucleus. Depending on the preoperative MRI, it was decided in some cases to record with three or four microelectrodes rather than five.

Magnetic resonance imaging targeting

The latest MRI Conditional (DBS) devices are making new inroads into the treatment of movement disorders like Parkinson`s disease and dystonia. The advent of `MRI Conditional Scan System` has enabled patients with DBS to safely undergo MRI full body scans. Deep Brain Stimultion (DBS) neurological procedure, is recognized treatment modality with proven effectiveness for movement disorders like Parkinson`s disease (PD), dystonia, Huntington`s disease and even depressions and epilepsy. In patients with DBS, MRI is paramount importance clinical research tool in analyzing electrode location, documenting postoperative complications and investigating novel symptoms. MRI scans have become a diagnostic standard of care, allowing physicians—doctors to detect a wide range of health conditions by viewing highly detailed images of tumours, internal organs and cell components of the brain, blood vessels, joints and muscles using strong magnetic fields and radio frequency pulses to create images of structures inside the body. Having already benefitted countless patients, the number of indications for DBS is steadily increasing and the technology has been formally approved to help patients gain control over movement disorders. World-wide, it is estimated that approximately 60 million MRI procedures are performed each year. 23, 24 Most patients who qualify for DBS have conditions, which may require MRIs post implant. Despite MRI being one of the most necessary diagnostic procedures in a majority of patients, its use in DBS patients had been discouraged earlier, due to safety concerns. At present seven out of ten DBS patients require MRI scans, a huge ratio. 23, 24, 25, 18 This new feature will allow patients to undergo MRI scaning without turning off the device or compromising on the benefits of the therapy. A change in settings of the device, and the patients can continue to receive therapy during MRI scans. For patients waiting to get their dBS implantation done, this is a blessing which will make the treatment more accurate, effective and safe. So with 60 million MRI procedures already being performed every year, this new feature is undoubtedly a feather in the cap of the DBS technology and a boon for patients waiting to get these implants done.

MRI is commonly the method of choice to image the body to diagnose disease or monitor existing conditions, but MRI use has often been limited in patients receiving DBS therapy and patients receiving. This is mainly due to not clearly visible STN neurons on MRI. However, DBS therapy can now receive more advantages of MRI Technology (John Thornton, 23). There are at least two major determining factors for an acceptable therapeutic outcome: patient selection26 and the accuracy of targeting of the relatively small STN. 27 The latter requires a state-of-the art stereotactic approach, adequate imaging facilities, and a detailed neurophysiological mapping of the target area. The preferred area within the STN is the motor part (thought to be located dorsolaterally in the STN), which can, be to some extent, identified by intraoperative multi-unit signal activity analyses, and MRI-based tractography. 28, 29

While the STN could not be visualized on MRI images when modern DBS of the STN surgeries started in Grenoble in 1993, nowadays its visualization has become a routine procedure for most centres offering DBS for patients with PD. While using intraoperative electrophysiology, was evident in the beginning, now it is questioned whether it still has an essential added value. In this opinion article, we aim to provide an answer on the question whether or not electrophysiology still has a clinically relevant role in this era of advanced neuroimaging technology, which enables us to visualize both function and anatomical structure (structure anatomy).

The discussion of whether or not to use intraoperative microelectrode recording (MER) is not a new one. 30 This discussion was perhaps less vivid when modern DBS started to be applied in patients with PD. The STN was an invisible target on MR images in most centres and MER was considered very helpful to find and delineate the boundaries of the target. 31, 32, 33 Since then things have changed. However, currently the STN can be directly visualized on T2 weighed and susceptibility weighed MR images. The imaging field progresses rapidly further with ultra-high field imaging modalities becoming now available for patients. 34

It is more than 15 years ago that that the visualization of the STN for DBS surgeries was described. 35 Mostly, T2 weighed and inversion recovery MRI sequences have been used. In most of the patients, the predefined target on T2 weighed MR images was chosen for implantation after intra-operative electrophysiology and test-stimulation. 36, 37, 38 This meant that in most patients MRI images could reliably show the STN, except for the y axis, in which microelectrode recording (MER) indicated that the STN extended more interiorly than suggested by MRI. 39 Detailed volumetric analysis of MER-determined borders of the STN and MRI- defined borders in 22 patients (44 STN’s), showed that MER-determined borders of the STN were exceeding the MRI signal.40 In addition, we examined the entry and exit borders of the STN on MRI images and with MER, using the probe’s eye trajectory.20 We found that T2 weighed MRI could reliably predict the electrophysiological entry and exit of the STN. Although these data confirm the accuracy of MRI in visualizing the STN, there are also limitations. There are known variations between the patients with respect to the x, y, and z planes, and the borders can sometimes be less clear, mainly toward the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr).39, 20

From Atlas-based to MRI Based Coordinates and from Single-electrode to Multiple-electrode Recordings

In our previous series of 55 patients with PD who underwent DBS of the STN, atlas- based coordinates were used and in about one third of the patients the predefined target (central trajectory) was used for final electrode implantation, after MER and intra-operative test-stimulation.41 With applying individually adjusted coordinates based on T2 weighed MRI, the central trajectory was chosen in about two-thirds of the patients20, 42, 21 (Tonge et al., in press). This has resulted in a clear reduction in operation time. Similar rates have been reported by others with atlas-based43 and MRI-based targeting coordinates.44 The change from 1.5 to 3.0 T has also improved the accuracy of targeting.45, 46 Another development has been the change of single-electrode to multiple-electrode intra-operative electrophysiological recordings.20 The latter provides more detailed information about the electrophysiological boundaries of the STN; however, implantation of several electrodes at one time might increase the risk of bleeding. We found that the simultaneous implantation of multiple electrodes did not cause more bleedings or other major intracranial complication. The use of multiple electrodes resulted in better motor results when compared with patients who underwent DBS of the STN guided with a single recording electrode. There are reports, however, suggesting increased risk of hemorrhage due to MER.47, 29, 48, 30

Is intra-operative electrophysiology necessary to find the STN? The answer is no based on the advances in MRI technology. In line with this experienced DBS centres have shown good outcome with a MRI-guided approach.49, 50 So should we abandon MER then? In our centers, we have decided not to abandon it for a number of reasons. Even in experienced centers, in about two-thirds of the cases, the predefined target is chosen for final implantation. In one-third, an alternative trajectory is needed. With MER, alternative trajectories are immediately available. The trajectory with the second longest and, if needed, the third longest STN activity can be used as alternative trajectories. Two other less common reasons to use intra-operative electrophysiology can be an unexpected error in the stereotactic approach or a shift caused by excessive CSF leakage or a hematoma.44 The problem with targeting subthalamic nucleus is that it is relatively a small biconvex lens structure almond lens-shaped component (Figure 4) and not clearly identified on the MRI due to lack of contrast between the STN and the surrounding structures.51, 52 The STN can be visualized on the MRI but other methods such as Lozano’s technique where a position 3 mm lateral to the superolateral border of the red nucleus is targeted have been studied and found to be effective areas for stimulation.53

There are five different (D1–D5) DA receptors are defined, namely, globus pallidus (both externus and inturnas), putamen, substantia nigra, subthalamic nucleus, and thalamus as shown in(Figure 5).

As the MRI/fMRI techniques are not absolutely perfect, use of electrophysiological techniques such as microelectrode recording from the subthalamic nucleus as well as intra-operative stimulation have helped in clearly distinguishing the STN. Microelectrode recording can identify subthalamic neurons by their characteristic bursting pattern and their signals (the MER signals of STN) clearly identify the nucleus form the surrounding structures. On table stimulation is studied to ensure that the there is optimal benefit with the least side effects and this is the final test to ensure the correct targeting of the STN. All these techniques are normally used in combination during targeting, although the individual role of each modality is still unknown Deep brain stimulation of bilateral subthalamic nuclei is an effective mode of operandi in subjects with idiopathic Parkinson`s disease. Accurate targeting and placement of microelectrodes are important for optimal results after STN-DBS. Stereotactic assessment, intra-operative microelectrode recording and intra-operative stimulation effects have all been used in targeting, although the individual role of each modality is still not known.

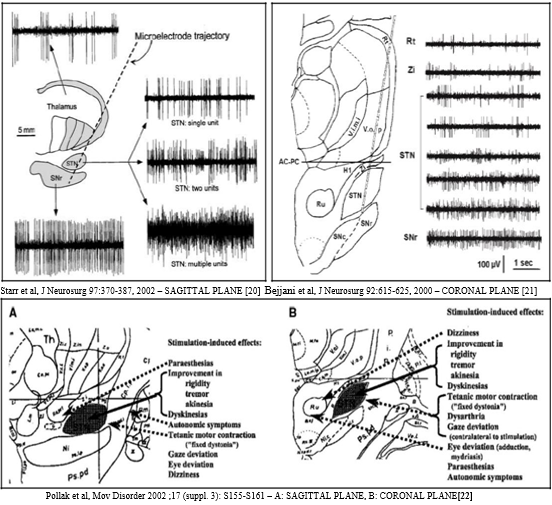

Microelectrode Recording

Although the structural anatomic organization may provide some clues as to what might be the function of basal ganglia circuits, inference of function from anatomy is exploratory or speculative. One approach to studying the function of an area of the central nervous system is to record the electrical activity of individual neurons with an extracellular electrode in awake, behaving animals. Other approaches involve inferences of neuronal signaling from imaging studies of blood flow and metabolism, or of changes in gene expression. By sampling the signal of a part of the brain during behavior, one can gain some insight into what role that part might play in behavior. Neurons within different basal ganglia nuclei have characteristic baseline discharge patterns that change with movement. If an animal is trained to perform a task consistently, the activity of single neurons can be correlated with individual aspects of the task performance. Furthermore, the timing of neural activity in one part can be compared to the timing of another and to the timing of the movement. 1 This section emphasizes signals recording in the STN neurons—neural components of basal ganglia (an organ of the brain) that are correlated with movement or the preparation for movement at the micro-level with MER system. Even though microelectrode recording (MER) reveals the electrical activity and patterns of different brain (sub) structures, it is difficult to determine whether MER has a positive effect on the clinical and/or diagnostic outcome of deep brain stimulation (DBS) treatment. 54, 55 Ultimately, it would be important to know whether the use of MER has a positive effect on clinical outcome and whether the influence that MER has had on the choice of the target has been beneficial. These questions, however, are very difficult to answer since the clinical outcome is determined by many more factors than the use of MER alone. Therefore, this has not been the aim of the current study. As a first result of this longitudinal study on MER during DBS, it was investigated to what extent the use of MER influences the DBS surgical procedure. The relative contribution of the physiological data obtained by MER and the clinical data obtained by intraoperative test stimulation to the selection of the final position for implantation was evaluated. Furthermore, we examined to what extent the activity pattern obtained from the MER corresponded with the target position based solely on three-dimensional functional magnetic resonance imaging. Finally, it was studied whether the target position based on the best MER activity matched the finally chosen location for electrode implantation based on intraoperative test stimulation. Figure 6 shows the typical modelled emblematic MER recording of STN. 56, 57, 58

Saara M. Rissanen et.al,3 worked on the objective methods for quantifying the DBS and presented a principal component (PC) -based tracking method for quantifying the effects of DBS in PD conditions by using EMG and acceleration measurements—kinematic analysis. Ten parameters capturing PD characteristic signal features were initially extracted from isometric EMG and acceleration recordings. Using a PC approach, the original parameters were transformed into a smaller number of parameters, i.e., PCs. Finally, the effects of DBS were quantified by examining the PCs in a low-dimensional feature space. The EMG and acceleration data from 13 PD subjects (patients) with DBS on and off and 13 healthy age-matched controls were used for analysis. The effects of DBS on elbow flexion and extension movements were analyzed separately. Clinical evaluation of subjects showed that their motor symptoms were effectively reduced with DBS. The analysis results showed that the signal characteristics of 12 subjects were more similar to those of the healthy controls with DBS on than with DBS off. These observations indicate that the PC-based tracking method can be used to objectively quantify the effects of DBS on the neuromuscular function of PD patients. Further studies are suggested to estimate the clinical sensitivity of the method to different types of PD. Those signal features were parameters of nonlinear dynamics, the coherence between EMG and acceleration, and the amplitude of acceleration. The hypothesis of their study was that the developed method is capable of quantifying objectively the effects of DBS on patients with PD. In that case, the measurement characteristics of patients are more similar to the measurement characteristics of the healthy controls with DBS on than with DBS off.

Amirnovin et al59 studied the effect of microelectrode recording (MER) in targeting STN in 40 subjects. The predicted location (pre DBS MRI) was used in 42% of the cases but was modified by MER in the remaining 58%. By using MER, an average pass through the subthalamic nuclei (STN) of 5.6 mm was achieved compared to 4.6 mm if central tract was selected as per imaging. Use of MER increased the path through the STN by 1 mm, increasing the likelihood of placing the DBS electrode squarely in the STN, which is a relatively small target.59 Bour et al60 analysed the effects of micro recording in 57 subjects with STN DBS and 28 subjects with GPi DBS. For the STN, the central trajectory was chosen for implantation in 50% of the cases and for the globus pallidus internus (GPi) in 57% of the cases. In 64% of STN DBS cases, the channel selected had the longest segment of STN MER activity. For the GPi, this was the case in 61%.60

Typical Trajectory

A trajectory with target situated at the base of the STN and using a lateral angle of 15º degrees and anterior angle of 60º degrees will typically bump into the following structures Table 4 (starting at 10-15 mm above target).

Table 4

Base of the STN using a lateral angle of 15º and anterior angle of 60º revealing the structures

Positioning of Deep Brain Stimulator (DBS) Targets from Micro Electrode Recording (MER)

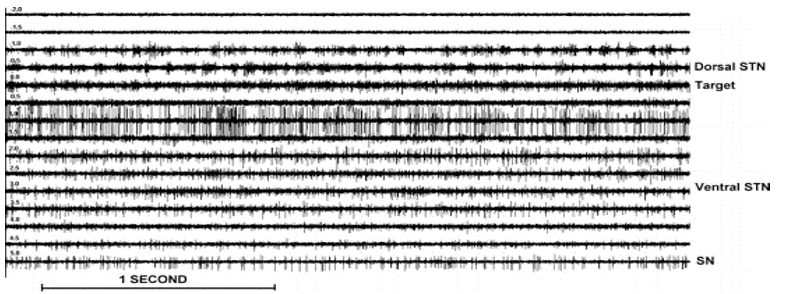

The STN was clearly distinguished from the dorsally (i.e., back spinal part of the body) located zona incerta (i.e., horizontally elongated region of gray matter cells in the subthalamus below the thalamus. Its connections project extensively over the brain from the cerebral cortex down into the spinal cord) and lenticular fasciculus (field H2) by a sudden increase in background noise level and increase in discharge rate typically characterized by rhythmic bursts of activity with a burst frequency between 5Hz to 20 Hz.61 Deeper into the STN rhythmic burst activity shifted to higher frequencies lying between 15Hz to 40 Hz. Also, more irregular firing units were observed. The ventral border of the STN was recognized by a decrease of background noise and a decrease of multi-unit activity across a distance of 0.5 to 2 mm, and, passing the ventral border of the STN, a sharp decrease in background firing was found, with more regular firing units (mean fire frequency 20 Hz to 80 Hz) of the substantia-nigra (SN) (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Single/multi-unit activity of STN for various depths (−2 to+5mm). Note that the negative values correspond with positions above the target. The superficial part of the STN (−1 to 0 mm) is clearly recognized by an increase in background noise and a sudden increase in discharge rate characterized by rhythmic bursts of activity in this case from 15 Hz to 25 Hz. Deeper layers of the STN (+1.5 to 3.5 mm) show a more irregular high-frequency discharge pattern. SN activity (+5 mm) consists of a low-frequency tonic discharge.

In case the central electrode was selected for implantation of the electrode, this was also the channel with best MER in 78% for STN and in 76% for GPi. The final electrode position in the STN, if not placed in the central channel, was more often lateral than medial to the calculated target [10% (10/98) lateral; 6% (6/98) medial] and more often anterior [24% (22/98)] than posterior [(10% (10/98)]. The mean and standard deviation of the deepest contact point with respect to the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based target for the STN was 2.1±1.5 mm and for the GPi was −0.5±1.2 mm.60

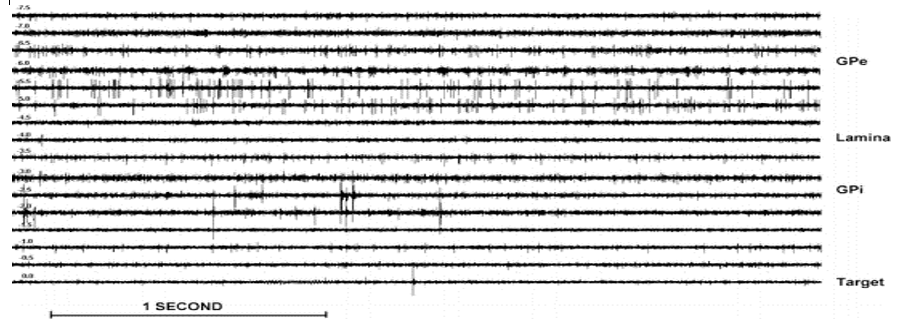

The GPe could be delineated from the dorsally located putamen by an increase in multi-unit firing activity at a depth varying from −12 to −9 mm from the MRI-based target. At advancing depth between −7 to −5 mm, the medial medullary lamina separating the GPe from the GPi was reached. The presence of this lamina was characterized by a decrease in electrical activity and had a thickness of 1 to 2 mm. In the vicinity of the medial medullary lamina, border cells were often recorded with a tonic regular discharge frequency between 5Hz to 30 Hz. The GPi was usually more densely packed with neurons reflected by a more intense multi-unit activity than observed in the GPe. Also, bursting and pausing activity (dystonia) and tremor-related (in PD) activity were frequently observed in the GPi. Within the GPi, regularly, another lamina at about −2 mm could be observed. The bottom of the GPi was recognized by a sudden decrease in background noise and multi-unit activity as the optic tract was approached (Figure 8). Data segments were analyzed off-line for stability by visual inspection. When volatility or movement/ vibration or electrical artifacts were observed, the longest stable section was selected from the recording, discarding the rest.

Figure 8

Single/multi-unit activity of GPi for various depths (−7.5 to 0mm).Note that the negative values correspond with positions above the MRI-based target. At −4.5 and −4 mm clearly, the lamina between the external and internal segment of the GP can be observed. The bottom of the GPi is reached at 0 mm

Objectives

The prime objective is to design a computational modelling and using the model to develop a new diagnostic and/or clinical experiment for the effective neuro medical diagnostics for the end users. To investigate and evaluate the potential benefits of microelectrode recording (MER) focused machine

To improve the motor symptoms i.e., reduce tremor, rigidity and bradykinesia, and to implant the electrode correctly to record the massively curved data streams (voluminous signals) of neurons of nuclei with MER and to study the effectiveness (and thus efficiency) of microelectrode signal recording of PDs in determing the final tract for placing DBS electrode during bilateral STN-DBS, and to evaluate the changes in STN neuronal activity in PDs. Finally, to formulate a new model for the brain`s circuitry to expose a full-bright target for the Parkinson`s diseased (PD) conditions.

Methods

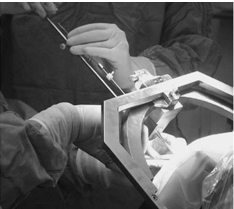

An investigative fusion study was carried out at a tertiary care hospital with a dedicated movement disorder unit from South India. 46 subjects (Parkinson`s diseased conditions—patients) with diagnosis of PD as per United Kingdom Parkinson disease society brain bank criteria were included. All the subjects were willing to undergo procedure and fulfilled the following criteria to be eligible for STN-DBS i.e., they had disease duration of 6 years or more, good response to levodopa, able to walk independently in drug “on” state and had normal cognition. All subjects who were wheelchair or bed bound, had dementia or severe psychiatric disturbances were excluded. Surgery was planned using a versatile tool called CRW frame (Lateral (X), A.P(Y), Vertical (Z), Ring and Arc) with an MRI protocol using Framelink software with 5 channels. The frame was applied to awake the subject. Oral sedation was administered 30 minutes prior to the procedure (2 tablets of Percocet and 5 mg of Valium). The subject remains alert with this regimen, which usually eliminates much of the discomfort of frame application. The scalp was always cleaned with spirit swabs and the subject sits up. An assistant stood behind the subject, holed the stereotactic base ring, stabilizing his hands on the subjects shoulders. It is important to ensure that the subjects nose will clear the ring and the overlying localizer after the application was completed. The Neurosurgeon was kept the target in his mind and adjusted the frame link accordingly. Local anesthesia was injected through the posts, and the pins were inserted until the finger was tight. A gentle tug on the frame checked the placement. The MRI images were transferred on the operating computer room and the rods were identified. With the help of the computer, the coordinates were entered for each rod and for the target on the slice of interest and then the coordinates were set accordingly. Anterioposterior, lateral and vertical settings for the stereotactic ring and arc were derived. Meanwhile, the subject was positioned (Figure 9). Anesthesia with intravenous sedation was given.

Duration of the phantom base setting was 5 minutes to the procedure has given the assurance to surgeon and the target was reached using the spatial settings. The Arc on the phantom base in the neurosurgical theatre operating room is shown (Figure 10).

The base was sterilized which added the measure of protection against infection. The coordinates were set phantom ring and arc, and a pointer is adjusted to the fixed depth from the probe holder to the target (17cm). After verifying the accuracy of the targeting, the surgical field prepped and draped, the arc was transferred to the base ring. The arc cantered design of the CRW system allowed for entry point was accessed through the arc and instrument holder. It was noticed that for temporal approaches, mounting the arc at 90º to the usual orientation given the complete exposure of the area of interest. Depending on the target, the skull was drilled. The instrument was introduced to the desired depth and the subject was examined to rule out new neurological deficits. The insertion of the electrode is shown in Figure 11.

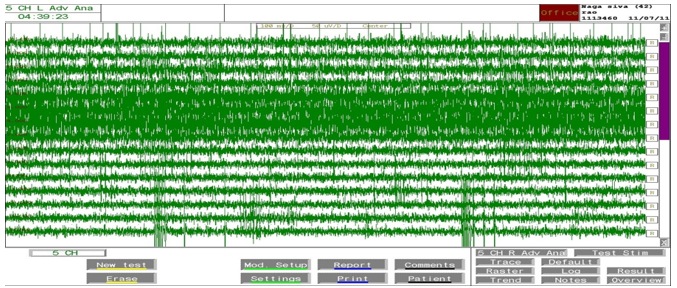

Stimulation of the functional target was done. The microelectrode recording was then performed in all subjects extending from 10 mm above target to 10 mm below STN. Final target selection was based on the effects and side effects of macrostimulation and confirmed by post operative MRI. Based on the frame, the skull is drilled and 5 microelectrodes are introduced into the brain through five channels –central, anterior (front), posterior (back), medial (near midline) and lateral (away from midline). Recording is started from 10 mm above the target determined by the MRI and is extended 10 mm below. Surgery was performed in all by a qualified neurosurgeon. Stereotactic targets were acquired using a specialized system with a stereotactic frame (CRW) which has a luminant MR localizer. The targeting was performed according to Lozano’s technique – 2mm sections are taken parallel to the plane of anterior comissure-posterior commissure line and at the level with maximum volume of red nucleus, STN is targeted at 3 mm lateral to the antereo-anterior-lateral border of red nucleus. The co-ordinates are entered into a stereo-calc software which gives the co-ordinates of the STN. For co-ordinates and angles, the standard approach can be viewed in the next section. Another neuro navigation frame link software is also used to plot the course of the electrodes and to avoid vessels. The surgery is performed with two burr holes on the two sides based on the co-ordinates. Five channels with are introduced with the central channel representing the MRI target while medial (nearer the centre) and lateral (away from the centre) are placed in the X-axis while anterior(front) and posterior (back) are placed in the Y-axis to cover an area of 5 mm diameter. Stimulation is done with 130Hz, 70 microsecond pulse width and response is seen with increasing amplitude. Whichever channel shows the best response that is chosen. The first level of MER recording is used to determine the depth of DBS electrode placement - that is if recording starts at -5 levels, the lead is placed from that level. The following Figure 12 obtained with the MER focus. The STN was detected by a high-noise with a larger baseline and irregular discharge patterns of multiple frequencies. The STN was clearly distinguished from the dorsally located zona incerta and lenticular fasciculus (field H2) by a sudden increase in background noise level and increase in discharge rate typically characterized by rhythmic bursts of activity with a burst frequency between 20 to 35 Hz.

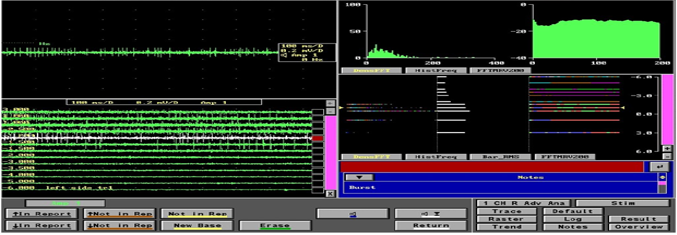

Figure 12

The signal patterns (single and multi neural unit activity) of STN neurons for various depths: -4mm to +10mm. It may be noted that the superficial part of the STN is recognized by an increase in the background noise and a sudden increase in discharge rate characterized by the rhythmic bursts of activity with higher frequencies (neurons 3, 4, 5 and 6). The negative (-4 to -1)) values correspond with positions above the MRI-based target. Deeper layers of the STN show a more irregular high frequency discharge patterns.

Intra-operative recording was performed in all 5 channels. All five microelectrodes are slowly passed through the STN and recording is performed from 10mm above to 10mm below the STN calculated on the MRI. STN IS identified by a high noise with a large baseline and an irregular discharge with multiple frequencies. The following Figure 13 shows the microelectrode recording which is obtained from the STN.

Figure 13

Image of the microelectrode recording— four windows are displayed in this picture. The panel in the top left shows recording in a single level in a single channel; the panel in the bottom left shows the recording in the central channel over 11 mm and shows the typical firing pattern with irregular firing and broad baseline noted from -1.00 level; the top right shows the typical histogram frequency and the Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT) graphs of a typical STN neuron; the bottom right shows the same in a linear curve fashion.

The channel with maximum recording and the earliest recording were recorded on both sides. Intraoperative test stimulation was performed in all channels from the level at the onset of MER recording. Stimulation was done at 1mv, 3mv to assess the improvement in bradykinesia, rigidity and tremor. Appearance of dyskinesias was considered to be associated with accurate targeting. Side effects were assessed at 5mv and 7mv to ensure that the final channel chosen had maximum improvement with least side effects. Correlation was assessed between the aspects of MER and the final channel chosen in 46 subjects (92 sides, i.e., right hemisphere and left hemisphere of the brain).

Standard Coordinates and Approach Angles

Burrhole – usually directly on the coronal suture or up to 2 cm anterior to it and 3 – 4 cm lateral to midline. Anterior Angle: circa ~ 60 degrees, Lateral Angle: circa ~15 degrees lateral from midsagittal plane. It is highly recommended to select angles around these typical values in such a way that the whole trajectory from entry to target is far enough away from any visible sulcus, blood vessel and the lateral ventricle. On X-axis: 12 mm lateral from ACPC (anterior commissure-posterior commissure) line On Y-axis: 3-4 mm posterior from mid-ACPC. On Z-axis: 5 mm below ACPC line

MER – our NIMS experience

To date 270 Subjects have undergone DBS at our NIMS tertiary care center. Medtronic system lead point - 5 channels MER is done in all. MER data of 46 subjects who underwent DBS from August 2008 to Feb 2011 were analyzed.

Subjects characteristics: Mean age was 58.1 + 9.1 years, Mean disease duration was 8.8 + 3.64 years, Mean UPDRS score in off state 52.7 +10.6, Mean UPDRS score in on state was 13.4 + 5.0

Findings of Microelectrode Recording

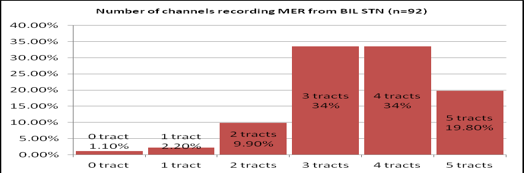

46 subjects were included in the study with their mean age of 58.1 + 9.1 years and with a mean disease duration of 8.8 + 3.64 years. Out of 5 channels, STN microelectrode recordings were detected in 3.5 +1.1 on right side and 3.6 +1.04 on left side. Figure 14 shows the percentage of people with the number of channels showing microelectrode recording. Final tract selected were most commonly central seen in 42.3% followed by anterior in 33.7%. Concordance of final tract with the channel having the highest recording was 58.7%, with channel showing maximum width of recording was 48% and with either was 64%. Absence of any recording in the final tract chosen was seen in 6.52%. Out of the six patients, one patient had no recording and lead was placed in central channel. Two patients had medial, 2 anterior and 2 central channels as their final tract. This was selected based on macrostimulation. Mean number of channels in which STN MER was detected (out of 5 multiple channels)

Right side= 3.5+1, Left side =3.6 + 1.04

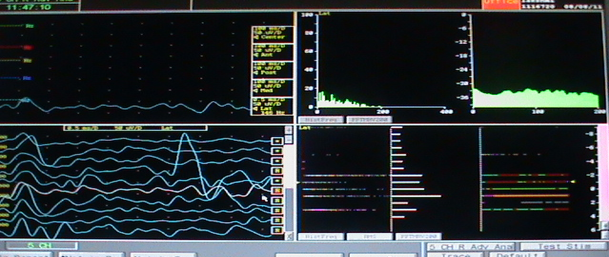

The 92 sides (bilateral both right and left hemispheres) of 46 subjects were assessed and the concordance rate with the superior most signal strength (amplitude) and maximum width of recording and the combination were analyzed. Final channel selected were: Central in 39/92 -42.3%, Anterior in 31/92 -33.7%, Medial in 15/92-16.3%, Posterior- 4/92 -4.3%, Lateral in 3/92-3.2%, Concordance with the highest recording (with the track chosen) was seen in 58.7%, Mean Maximum length of recording was 5.3 + 1.3 mm, Maximum length of STN was in the chosen track in 48%, Concordance with either highest recording or maximum length was noted in 64% The following image (Figure 15) shows the single unit microelectrode recording— four windows are displayed in this picture. The panel in the top left shows recording in a single level in a single channel; the panel in the bottom left shows the recording in the central channel over 11 mm and shows the typical firing pattern with irregular firing and broad baseline noted from -1.00 level; the top right shows the typical histogram frequency and the Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT) graphs of a typical STN neuron; the bottom right shows the same in a linear curve fashion.

Figure 15

The single unit microelectrode recording— four windows are displayed in this picture. The panel in the top left shows recording in a single level in a single channel; the panel in the bottom left shows the recording in the central channel over 11 mm and shows the typical firing pattern with irregular firing and broad baseline noted from -1.00 level; the top right shows the typical histogram frequency and the Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT) graphs of a typical STN neuron; the bottom right shows the same in a linear curve fashion.

In 28 subjects, the final tract did not correspond either to the tract with highest MER signal recording or the maximum width of microelectrode-recording:

13 ubjects had central tract, 8 had anterior, 7 had medial tract as final tract, Mean length of, MER recording in these channels was 2.3+ 1.8 mm

MER Experimental Analysis and Discussion

We assessed the role of microelectrode stimulation in selection of the final channel. Compared to the anatomical localization based on MRI where the final tract was seen only in 42.3% the microelectrode recording was associated with final channel in 64 %. This is similar to a previous study wherein by using MER, an average pass through the STN of 5.6 mm was achieved compared to 4.6 mm if central tract was selected as per imaging.59 93.48% of subjects showed STN neurons recording in the final channel chosen. Absence of any recording from STN in the final tract selected was noted in 6/92-6.52%. Out of the six subjects, one subject had no MER recording in any of the five channels and lead was placed in central channel. 2 subjects had medial, 2 anterior and 2 central channels as their final tract. This was selected based on macrostimulation. MER by itself is not a complete tool to clearly distinguish—discriminate the optimal target as the line of the DBS lead may not correspond to the axis of the STN. Further the impedance of the microelectrode may vary as they may be influenced by the brain tissue and may not show a clear recording. Unperturbed MER can definitely confirm the clear position of the electrodes and bolsters the confidence of the neurosurgeons that they are in the target. Further the availability of microelectrode recording results in a vast data regarding the functioning on the neurons situated deep in the brain and may help in further untying mysteries of the brain. When discriminating between subjects or between different states of the subjects, such as between DBS on and off, on the basis of MER signal measurements, often, there are many signal parameters that can capture essential features in the signals. Each of the parameters describes one feature (e.g. the amplitude, complexity, etc.) in the measurements. It could be possible to examine the statistics of single parameters. However, often a combination of several parameters works better in discrimination and a dimension reduction technique, such as the PC approach, can be used to capture the essential and ignore the irrelevant information in the combination of variables. In clinical use, we could then use the known PD related indexes for quantifying objectively the effects of DBS treatment in PD.

Cost of a complete DBS Surgery

In a US based review, the average cost for STN-DBS with MER was $26,764.79 per subject for unilateral, $33,481.43 for simultaneous bilateral, and $53,529.58 for staged bilateral. Unilateral DBS the cost of MER was $19,461.75, ↑ total cost by 267%. For simultaneous bilateral DBS, the MER costs $20,535.98, ↑ total cost by 159%, and for staged bilateral DBS, the MER costs $38,923.49, ↑ total cost by 267% 62. Proposed equipment (in US $ Dollars): MER FOCUS Machine: $107692, Stereotactic frame: $100000, N-VISION: $ 10800. Stardrive unit to advance MER: $ 49250, (Fine resolution), Neuronavigation framelink software: $ 46150, and A/D Converters: $ 5000

Conclusions

In Parkinson`s disease, there is a decreased dopaminergic cell output from the SN which changes the firing patterns of many nuclei. One of the consequences is an increased firing from subthalamic nucleus which by stimulating globus pallidus interna causes inhibition of thalamus and cortex causing slowing of voluntary movements. The simplistic view was supported by the fact that high frequency current delivered to subthalamic nuclei (STN) or globus pallidus interna (GPi) which caused their inhibition improved symptoms. It is now known that there is a significant change in the firing pattern and a reorganization of the entire basal ganglia with DBS. Microelectrode recording from STN has identified a specific high frequency irregular larger amplitude firing patterns seen only decrease state and this is used to detect the STN neurons during surgery. The DBS is a stereotactic based functional neurosurgery and as the STN cannot be clearly visualized on the MRI and the targeting based on Lozano`s method is indirect (3 mm lateral to the lateral and superior margin of the red nucleus). MER gives proof of the correct positioning of the electrodes. Thus, MER confirms the presence of abnormal STN neurons. Clinical evaluation of PD subjects showed that their motor symptoms were effectively reduced with DBS. The analysis results showed that the signal characteristics of 42 subjects showed varied results. These observations indicate that the MER based tracking method can be used to objectively quantify the effects of DBS on the neuromuscular function of PD subjects. Further studies are suggested to estimate the clinical sensitivity of the method to different types of PD. Microelectrode recording is useful to identify and confirm the tract in which DBS electrodes are placed and is most useful in determining the depth of electrodes placement but has to be taken in consideration with effects seen on macrostimulation. Further, we write that the MER with DBS and electrophysiological techniques has a clinically relevant role in the era of advanced neuroimaging technology, which enables us to visualize both function and anatomical structure. It may be concluded that, the MER signal measurements are potentially useful for quantifying the effects of DBS on the neuromuscular function of PD subjects. These measurements in combination with the latent variate factorial method, a mathematical analysis which is a principal component (PC) based tracking method can be used to quantify the effects of DBS objectively, cost-effectively and non-invasively and in further studies, the presented approach could be tested in helping the adjustment of DBS settings. In addition, the sensitivity of the presented method to different types of PD should be estimated more carefully in further clinical and/or diagnostic studies.